Margaret Barker, a 78-year-old retired headmistress attended the walk in centre. She complained of feeling unwell. She said she had a headache and felt ‘fluish’ and had been off colour for a few days. She said she had a small itchy rash on her abdomen. Mrs Barker had herpes zoster also known as shingles. This article explains how older people are increased risk of shingles and its complications. It will enable readers to recognise the clinical features of shingles, be aware of current treatments and how vaccination can protect older people from this distressing condition.

What is shingles?

Shingles is a painful blistering rash caused by reactivation of varicella zoster virus, the chickenpox virus. It is correctly known as herpes zoster.1

The term shingles is derived from the Latin word cingulum, which means belt or girdle. The term herpes zoster is derived from the Greek words herpein meaning to creep, and zoster meaning girdle or belt. Both Latin and Greek terms describe the way the rash creeps across a dermatome (an area of skin supplied by a single spinal nerve). The shingles virus causes the nerve cells on a spinal nerve to become inflamed.

Individuals are first exposed to the herpes zoster virus by contracting chickenpox (usually in childhood). When

a person recovers from chickenpox the virus remains in the spinal nerves in a dormant form. Healthy adults do not develop shingles because the immune system keeps the virus dormant.

When the immune system is compromised the virus re-activates. Figure 1 illustrates some of the risk factors.

The immune system becomes less effective with age and ageing therefore increases the risk of developing shingles2 – 68% of those with shingles are over 50. The risk of developing shingles increases by 1% every year between the ages of 50 and 75.3 Older people who are very depressed are even more likely to develop shingles because depression affects the immune system.4 Conditions such as human immunodeficiency disease (HIV), and lymphoma and medications such as steroids depress immune system and increase the risk of shingles.5

Another risk factor is the the use of statins. These drugs are used to lower cholesterol but are known to affect the immune system. Recent research examining the medical records of almost a million people over 13 years found the rate of shingles was 13% higher among users of statins than non-users. Among people with diabetes, the rate of shingles was 18% higher among statins users. They found that ‘treatment with statins is associated with a small but significantly increased risk of herpes zoster’.

The research suggests that around 10% of cases of herpes zoster in older people may have been triggered by statins. The authors estimated that not prescribing statins would have avoided 11.6% of the episodes of herpes zoster among older people. Further research is required to clarify the mechanisms through which statins reactivate shingles virus and whether younger patients are at risk.6 Prior statin use also leads to increased risk of developing shingles.7

Clinical features

Shingles is diagnosed on the basis of clinical features. Initially the person may complain of non specific symptoms such as headache, generalised aching, feeling unwell and may have a mild temperature. In those who have shingles a rash usually develops within 24 hours.

Around 10% of people with shingles develop ophthalmic complications.8 A small number of people who develop eye complications or neurological complications may not have a rash.9 People who have neurological or eye symptoms are at risk of ophthalmic complications and should be referred for appropriate medical advice.

Most people develop a rash and this normally appears along a single dermatome. At first the rash is red and there are tiny blisters-vesicles. It can be intensely itchy. In the next 72 hours the rash extends along the dermatome and the vesicles become larger as they fill with fluid. After 3-5 days they burst and the rash begins to dry and crust. The rash normally heals within 10-14 days but the skin can be pigmented. In white skins the skin can look brown, in dark skins the skin can look purplish. The pigmentation varies according to the person’s normal skin colour but it is noticeably different to the person’s normal skin colour.10

Treatment of shingles

Shingles is a painful, distressing condition. The aims of treatment are to reduce the severity of the attack, reduce pain, reduce discomfort, accelerate healing and protect others from infection risks.Early diagnosis and treatment is of crucial importance.

As shingles is caused by a virus, antiviral drugs are used to treat it. The most commonly used are acyclovir, famciclovir and valaciclovir. They prevent the virus from multiplying and limit the extent of the shingles attack. Antiviral treatment reduces rash, pain and post operative complications such as post herpetic neuralgia (PHN).11 Treatment should be commenced on diagnosis as antivirals are most effective when administered within 72 hours of the onset of the rash.12 If there are delays in diagnosis then antivirals should be prescribed if the person has severe pain or the rash is continuing to progress as the person will still obtain some benefit from treatment.13,14

Corticosteroids such as prednisolone may be prescribed for severe infection. The aims are to reduce pain and inflammation and also to increase the rate of healing. Evidence suggests that corticosteroids may reduce acute pain. However, there is little evidence that they improve wound healing.15 A Cochrane Review found little evidence that corticosteroids given in the acute phase prevented PHN.16 NICE recommends that oral corticosteroids are considered in the first two weeks following the onset of rash in immunocompetent adults with localised shingles if pain is severe, but only in combination with antiviral medication. The prescriber should use clinical judgment, taking into account the risks and benefits of corticosteroid therapy for each person.17

Pain can be treated with paracetamol alone or in combination with codeine or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (such as ibuprofen). It is important that these are taken regularly.17

Shingles itch and the patient may want to scratch, but this can cause bleeding and increase the risk of infection. Itching can be treated with anti-histamines. Older antihistamines such as chlorpheniramine (piriton) can cause drowsiness. Newer antihistamines such as cetirazine do not but they can be less effective in treating itching.

When a person’s skin is hot, itchy and uncomfortable they may benefit from topical therapy. Calamine lotion can be soothing. In some cases gauze soaked in tap water or in Burow’s solution (5% aluminium acetate) can cool and soothe the skin. It is also thought to have anti-bacterial properties and can reduce the risk of infection.

Normally the shingles rash dries and scabs over. If the rash is weeping non-adherent dressings may be required. They should whenever possible be held in place with a tubular cotton dressing rather than tape. Tape can damage delicate skin. Figure 3 illustrates treatment of shingles.

Infection control

The vesicles of a person with shingles contain the herpes varicella zoster virus. When these vesicles burst the liquid in them could potentially cause a person who has not had chickenpox to develop the condition. This could only occur if the person touches the fluid from the vesicles. The risk of developing chickenpox is very low.

Most people have already been exposed to chicken pox and acquired immunity as children. People with shingles should be advised to avoid contact with people who have not had chickenpox, particularly pregnant women, immunocompromised people, and babies younger than 1 month of age.

Reducing the risk of complications

There are two common complications of shingles. These are post herpetic neuralgia (PHN) and secondary infection.

Post herpetic neuralgia (PHN) is pain that continues after the acute episode of shingles has been treated and the rash has healed. Shingles causes the nerve root to become inflamed. This inflammation can damage the nerve and this damage can cause pain signals to be sent to the brain. The pain is described as ‘shooting, stabbing or burning’ and is usually localised, on one side of the body.18

Older people are at especially high risk of developing PHN.19 Neuropathic pain can be treated with a small dose of amitriptyline (10-20mg)20 (duloxetine, gabapentin and pregabalin can also be used).17 These medications prevent the nerves conveying the pain sensation to the brain so the person no longer experiences pain. Gabapentin and pregabalin can cause drowsiness, loss of balance and increase the risk of falls.21

Topical therapy can be used to treat pain. The medication is delivered in a plaster that is applied to the skin. Capsaicin the component of chilli peppers that causes burning is used in patch form. Capsaicin is likely to be used when other available therapies have failed. It should not be used repeatedly without substantial documented pain relief.22

Plasters containing 5 or 8 % lidocaine are also available. The 5% plaster is most effective.18 The plaster is applied to the painful area for around 12 hours and then has 12 hours without a plaster.23 People who apply these large patches to the limbs and trunk find them more acceptable than those who apply them to the forehead.24 Although current NICE guidance no longer recommends the use of topical lidocaine they are sometimes used in clinical practice.25

Secondary bacterial infection

When the shingles rash develops and the vesicles burst the skin is exposed and vulnerable to infection. The person should be encouraged to maintain good hygiene. Affected skin can be washed with clear water and patted dry gently. The person should wear soft, light clothing that is changed at least once a day. If the rash is weeping then non adherent dressings should be used and changed as necessary.Antibiotic therapy may be required to treat any secondary infection.

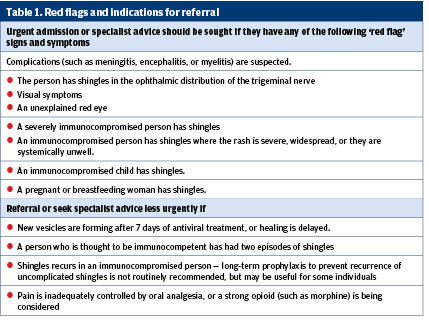

Red flags

Clinicians should use clinical judgment to decide who to refer to and the urgency, depending on the risk to the person and their clinical condition. Table one provides details of red flags.

Vaccination works

In 2012 around 250,000 people in the UK developed shingles and around 40% developed PHN.10 In September 2013 the NHS launched a vaccination programme and vaccination has led to a 35% reduction of shingles and 50% reduction in PHN. There were 17,000 fewer episodes of shingles and 3,300 fewer episodes of PHN.26 German research indicates that around 3 percent of people who develop shingles require hospital admission.27 If the figure is similar in the UK then vaccination has prevented around 510 hospital admissions.

Mrs Barker was eligible for the shingles vaccination and if she had had it then she would probably have avoided infection. The number of eligible people having the vaccine has fallen and it’s important to encourage your older patients to have it. It is offered to patients at the age of 70 or 78, or those born after 1942.

Vaccination reduces the risk of infection by around 72%, reduces the risk of PHN and prevents people from experiencing the debilitating effects of shingles and PHN. The incentives for nurses to increase uptake are crystal clear.

Linda Nazarko is a nurse consultant at West London Mental Health Trust

References

1. Oakley A. Shingles (Herpes Zoster). DermNet NZ, New Zealand. 2015.

http://dermnetnz.org/viral/herpes-zoster.html

2. Pawelec G. Hallmarks of human “immunosenescence”: adaptation or dysregulation? Immun Ageing. 2012. 9:1:15.

3. Yawn BP, Saddier P, Wollan PC, St Sauver JL, Kurland MJ, Sy LS. A population-based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction. 2007. Mayo Clin Proc.;82:11:1341-1349.

4. Irwin MR, Levin MJ, Carrillo C, Olmstead R, Lucko A, Lang N, Caulfield MJ, Weinberg A, Chan IS, Clair J, Smith JG, Marchese RD, Williams HM, Beck DJ, McCook PT, Johnson G, Oxman MN. Major depressive disorder and immunity to varicella-zoster virus in the elderly. Brain Behav Immun. 2011. 25:4:759-766

5. Wareham DW, Breuer J. Herpes zoster. British Medical Journal. 2007. 334: 1211–15

6. Antoniou T, Zheng H, Singh S, Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Gomes T. Statins and the Risk of Herpes Zoster: A Population-Based Cohort Study. 2014. Clin Infect Dis: 58(3):350-6

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3954107/

7. Chung SD, Tsai MC, Liu SP, Lin HC, Kang JH. Herpes zoster is associated with prior statin use: a population-based case-control study. PLoS One. 2014. 24;9(10):e111268.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4208841/

8. Opstelten W, Wand MJ, Zaal W. Managing ophthalmic herpes zoster in primary care. BMJ. 2005. 331(7509): 147–151.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC558704/

9. Nagel MA, Gilden D. Complications of Varicella Zoster Virus Reactivation. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2013. 15(4): 439–453.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3752706/?report=classic

10. Nazarko L. Shingles part one: guidance launched for vaccination. Nursing and Residential Care. 2013. 15:8:538-542

11. Lilie HM, Wassilew S. The role of antivirals in the management of neuropathic pain in the older patient with herpes zoster. Drugs Aging. (2003).;20:8:561-570.

12. Wood MJ, Shukla S, Fiddian AP, Crooks RJ. Treatment of acute herpes zoster: effect of early (< 48 h) versus late (48–72 h) therapy with acyclovir and valaciclovir on prolonged pain. (1998) J Infect Dis 178 Suppl 1: S81-S84

13. International Herpes Management Forum. Johnson RW, Whitely R, editors. Combating varicella zoster virus-related diseases. (2006) Herpes 13 Suppl 1: 1-41

14. Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. (2007) Clin Infect Dis 44 Suppl 1: S1-S26

15. Opstelten W, Eekhof J, Neven AK, Verheij T.Treatment of herpes zoster. Can Fam Physician. (2008). 54:3:373-377.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2278354/?tool=pubmed

16. Han Y, Zhang J, Chen N, He L, Zhou M, Zhu C Corticosteroids for preventing postherpetic neuralgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Mar 28;3:CD005582. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005582.pub4.

17. NICE. Shingles: Corticosteroids. CKS, London. (2016). https://cks.nice.org.uk/shingles

18. Nalamachu S, Morley-Forster P. Diagnosing and managing postherpetic neuralgia. Drugs Aging. (2012). 29:11:863-9.

19. Wareham D. Postherpetic neuralgia - Clinical evidence. British Medical Journal. (2005). 332: 147-151

20. Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, Cole P, Wiffen PJ. Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Dec 12;12:CD008242

21. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain: a systematic review. The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2009. Available at www.thecochranelibrary.com

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005454.pub2/C0D1708CC5D86CAA659D1D9E58F7A3A.f03t02

22. Derry S, Sven-Rice A, Cole P, Tan T, Moore RA. Topical capsaicin (high concentration) for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Feb 28;2:CD007393

23. Christo PJ, Hobelmann G, Maine DN. Post-herpetic neuralgia in Older Adults: Evidence-based Approaches to Clinical Management. Drugs & Aging. (2007). 24:1: 1-19

24. Nalamachu S, Wieman M, Bednarek L, Chitra S. Influence of anatomic location of lidocaine patch 5% on effectiveness and tolerability for postherpetic neuralgia. Patient Prefer Adherence. (2013). 18:7:551-557.

25. NICE. Neuropathic pain - pharmacological management. The pharmacological management of neuropathic pain in adults in non-specialist settings (Full NICE guideline). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London. (2013).

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG173

26. Amirthalingam, Gayatri et al. Evaluation of the effect of the herpes zoster vaccination programme 3 years after its introduction in England: a population-based study. The Lancet Public Health. (2017).

http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667%2817%2930234-7/fulltext

27. Hillebrand K, Bricout H, Schulze-Rath R, Schink T, Garbe E. Incidence of herpes zoster and its complications in Germany, 2005-2009. J Infect. 2014 Sep 16. pii: S0163-4453(14)00279-5.