One subject seems to dominate Britain in 2018, overshadowing any other political issue. From backstops to backstabbing, it’s rare a day passes without the UK’s exit from the European Union taking centre stage on the news.

The NHS and Brexit are inextricably linked. The widely debunked claim on Vote Leave’s ‘battle bus’ that leaving the EU would free up £350m a week to be spent on the NHS, was nevertheless seen to be a gamechanger during the campaign. Since the result, we have started to see what the real cost to the NHS will be, as numbers of EU nurses and GPs coming to work in the NHS have started to fall off.

One area which seems to have avoided great scrutiny is the effect of Brexit on public health. However, as an RCN briefing on the issue states, there are sector wide concerns that Brexit and the withdrawal of EU funding for public health measures will negatively impact the health of our population.

According to the RCN, the European Union plays a vital role in maintaining public health across all its member states. It facilitates collaboration on cross-border health threats, such as communicable diseases which can spread easily and anti-microbial resistance through the European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC). Other agencies controlling the supply of drugs and medication may also be affected.

The ECDC identifies and assesses risks posed to European citizens’ health from infectious diseases. Their work monitors potential outbreaks and recommends early warning response systems to protect our health. It is unclear currently what the ongoing relationship with ECDC will be both in terms of submission and comparison of UK data on infections/antibiotic resistance and the management of outbreaks in Europe that could impact on the UK.

NHS Providers’ evidence to the Commons Health Select Committee said that the benefits of maintaining the UK’s participation in the European Centre for Disease Control should be a central consideration in respect of the health implications of Brexit.

Preventing the spread of antibiotic-resistant ‘super-gonorrhoea’ and other infectious diseases in the UK could be compromised if the UK leaves the EU’s early warning system after Brexit without an effective replacement.

The Brexit Health Alliance – which brings together the NHS, medical research, industry, patients and public health bodies to safeguard the interests of patients and the healthcare sector – has warned that public health issues must be addressed upfront by Brexit negotiators.

Concern has been raised over the ramifications of leaving the ECDC. ‘We welcome the Government’s commitment to maintaining the highest standards of health protection after the UK leaves the EU,’ said Niall Dickson, chief executive of the NHS Confederation and co-chair of the alliance. ‘But we should be under no illusion – if we fail to reach a good agreement on the EU and UK’s future relationship, that could be a significant threat to public health. This cannot and should not be ignored.’

The consequences

The UK’s proximity to Europe and high levels of cross-border travel mean cases of infectious disease are regularly imported from other EU countries and vice-versa.

Outbreaks of measles in England and Wales have been repeatedly linked to ongoing outbreaks in countries in Eastern Europe while, in 2017, a multi-country outbreak of salmonella was linked to Polish eggs. Tracking these outbreaks requires collaboration between the United Kingdom and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, which also assesses risks from around the world, including the Ebola outbreak in Africa and an assessment of the risks to health at the upcoming football World Cup in Russia.

Another example is the recent case of a man who contracted ‘the world’s worst super-gonorrhoea’ and brought it back to the UK. Public Health England worked alongside the ECDC and the World Health Organisation to effectively track the infection. According to the Brexit Health Alliance, unless the UK can negotiate continued access to ECDC systems after 2019, there are likely to be delays in communication in cases of emerging risk or crisis management situations, resulting in delays in regulatory and other action.

‘Infectious diseases do not respect borders and we need to tackle them together. ‘It should be blindingly obvious to all concerned that that it is in all our interests to maintain these vital links,’ added Mr Dickson. ‘We need strong co-ordination in dealing with cross-border health threats and alignment with EU standards for food, safety of medicines, transplant organs and the environment.’ The negotiators have much on their minds but protecting the health of millions must be a priority, he said.

Concern has also been raised in local government, which currently provides a large number of public health services since the transfer of responsibility under the coalition government.

‘The UK is a world leader in tackling serious cross-border threats to health and has a well-developed health protection system highly regarded by European partners,’ said Cllr Kevin Bentley, chairman of the Local Government Association’s (LGA) Brexit Taskforce. ‘After formal exit from the Union, it is vital that the UK and EU maintain a high level of cooperation in these areas to ensure all countries continue to be able to effectively address health inequalities, tackle chronic diseases and protect against serious health threats.

Another area of concern that has been raised is the potential impact of staffing cuts on public health. A large number of NHS staff are from the EU, and any deal which required them to leave would have potentially enormous consequences on public health.

‘In some hospitals, one in five workers have EU passports – if there is a Brexit cliff-edge in migration, it will be the NHS going over it,’ RCN Chief Executive Janet Davies said. ‘The number of nurses coming from the EU has plummeted in the last 18 months and, rather than redoubling her efforts to attract more, Theresa May told them they have even fewer rights if they arrive during the transition period.’

Business as usual

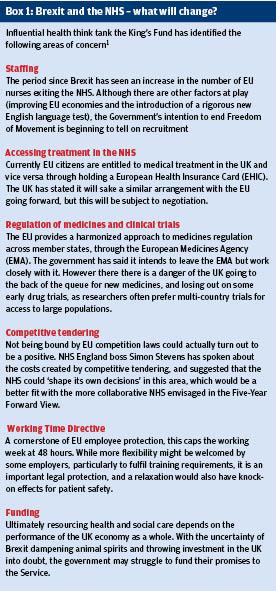

In evidence to the Commons Health Select Committee, Paul Macnaught, Director of EU, International and Public Health System at the Department of Health listed the biggest issues for the Department arising from the UK’s withdrawal from the EU as including workforce; medicines and devices regulation and the implications for the life sciences sector generally; reciprocal healthcare and health protection systems (for more info see box).

But Macnaught stated that as existing public health mechanisms would not be jeopardised by Brexit. ‘Obviously, we want to continue all aspects of co-operation with our partners and friends in the EU post-Brexit in order to reduce public health risks. It is incredibly unlikely that they will not want to do that, because it is as much in their interests as it is in ours,’ he said.

With the UK at such a critical point in its history, it is imperative that the government and its negotiators do not overlook such a vital area for our country’s future.

‘If the UK no longer had a relationship with the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, both UK and pEuropean health protection will be weakened due to reducing information exchange, increased risk of failures in surveillance and early warning, and increased risk of poorly informed decision making,’ said a European public health expert at the Faculty of Public Health.

While the media may fixate on the psychodrama, Brexit has brought to Westminster, it is easy to forget its very real effects on Britain’s wealth and health. Taking back control should not mean losing our grip on the public health challenges we will continue to face long after the Brexit bus has bowled out of town.

References

1. McKenna H. Brexit: the implications for health and social care. The King’s Fund 2017. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles...