You might also find these articles useful. Click to view

- Encourage your older patients to have the shingles vaccine

- The management of shingles

- Vaccinating against shingles

Shingles is caused by the Herpes Zoster virus and early identification and prompt treatment with antiviral drugs reduces symptoms and leads to reduced risk of ongoing nerve pain.1 Infection causes a painful blistering rash and it is more common in older people. It affects 3.5 per 1000 person-years among 50–54 year olds to 7.1 per 1000 person-years among 75–79 year olds.2 In England 50,000 people over the age of 70 develop shingles every year.3 Around 40% of people infected experience ongoing nerve pain lasting three months or longer and one person in a thousand over the age of 70 dies as a result of infection.4 People who are at greatest risk of infection can now be immunised. Immunisation can reduce the risks of shingles by 75%.5 Shingles is a painful blistering rash caused by reactivation of varicella zoster virus, the chickenpox virus. It is correctly known as herpes zoster.

The shingles virus causes the nerve cells on a spinal nerve to become inflamed. The term shingles is derived from the Latin word cingulum, which means belt or girdle. The term herpes zoster is derived from the Greek words herpein meaning to creep, and zoster meaning girdle or belt. Both Latin and Greek terms describe the way the rash creeps across a dermatome (an area of skin supplied by a single spinal nerve).

Individuals are first exposed to the virus by contracting chicken pox (usually in childhood).6 When a person recovers from chickenpox the virus remains in the spinal nerves in a dormant form. Healthy adults do not develop shingles because the immune system keeps the virus dormant. When the immune system is compromised the virus re-activates.

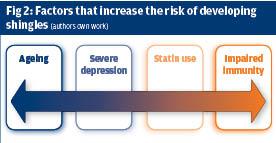

The immune system becomes less effective with age and ageing increases the risk of a person developing shingles.7

Depression increases the risk of developing shingles because it affects the immune system. Statins are known to affect the immune system increases the risk of shingles by 13%.8 In people with diabetes; the rate of herpes zoster was 18% higher among statins users.9 People who have taken statins in the past have a higher risk of developing shingles than those who have not)10 Diseases such as human immunodeficiency disease (HIV), and lymphoma and medications such as steroids depress the immune system and increase the risk of shingles and other infections.5

Clinical features

Shingles is diagnosed on the basis of clinical features. Initially the person may complain of non-specific symptoms such as headache, generalised aching, feeling unwell and raised temperature. Some people report that their skin tingles, is extremely sensitive or feels numb. A rash usually develops within 24 hours. This normally appears along a single dermatome.

A dermatome is an area of skin that is mainly supplied by a single spinal nerve.

Initially the rash is red and there are tiny vesicles (fluid filled blisters). The rash can be intensely itchy. In the next 72 hours the rash extends along the dermatome and the vesicles become larger as they fill with fluid. After 3-5 days they burst and the rash begins to dry and crust. The rash normally heals within 10-14 days however the skin can be pigmented and is noticeably different to the person’s normal skin colour.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) is a viral infection of the trigeminal nerve which supplies sensation to the eye surface, eyelids, forehead and nose. Around 10% of people with shingles develop ophthalmic complications. In HZO the skin of one side of the forehead and scalp is affected, along with the eye on the same side. Any part of the eye can be involved, but most commonly it is the eye surface, including the conjunctiva and the cornea. The cornea reacts to the infection in various ways; the most serious long-term effects result from damage to the corneal nerves, causing loss of sensation.11 A small number of people who develop eye complications or neurological complications may not have a rash.12 In primary care anti-viral treatment should be prescribed as soon as possible. In mild cases the GP or nurse practitioner may work with an optometrist to manage the condition. People who have moderate to severe HZO should be seen by an ophthalmologist.11

The importance of prompt treatment

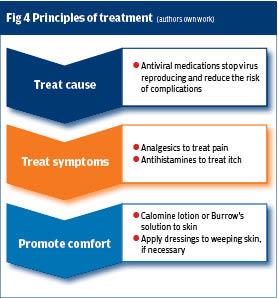

Shingles is a painful and distressing condition. Prompt treatment reduces severity of symptoms including initial pain and the risk of ongoing pain (post herpetic neuralgia). The principles of treatment are to treat the cause, treat symptoms and promote comfort. Figure 4 illustrates this.

Early diagnosis and treatment is crucial

As shingles are caused by a virus they are treated with antivirals. The most commonly used are acyclovir, famciclovir and valaciclovir. They prevent the virus from multiplying and limit the extent of the shingles attack. Antiviral treatment reduces rash, pain and complications such as post herpetic neuralgia (PHN).13 Treatment should be commenced promptly as antivirals are most effective when administered within 72 hours of the onset of the rash. If there are delays in diagnosis then antivirals should be prescribed if the person has severe pain or the rash is continuing to progress as the person will still obtain some benefit from treatment.13

Corticosteroids such as prednisolone may be prescribed for severe infection. The aims are to reduce pain and inflammation and also to increase the rate of healing. A Cochrane Review found little evidence that corticosteroids given in the acute phase prevented PHN.14 NICE recommend that oral corticosteroids are considered in the first two weeks following the onset of rash in people who have impaired immune systems and severe pain. They must be given in combination with antiviral medication, as steroids can worsen infection if given without treatment for the infection.15

Shingles can be very painful. Pain can be treated with paracetamol alone or in combination with codeine or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug . Analgesia should be given regularly and not as required.16

It is important to treat itching as scratching can cause bleeding and increase the risk of infection. Infection can increase the risk of PHN and itching can be treated by anti-histamines such as cetirizine and chlorpheniramine.2

Calamine lotion, gauze soaked in tap water or in Burrow’s solution (5% aluminium acetate) can cool and soothe the skin. Burrow’s solution is thought to have anti-bacterial properties and can reduce the risk of infection. Normally the shingles rash dries and scabs over within 10-14 days. If the rash is weeping non adherent dressings may be required. They should whenever possible be held in place with a tubular cotton dressing rather than tape which can damage delicate skin.

Infection control

Vesicles contain the herpes varicella zoster virus and contact with vesicle liquid could potentially cause a person who has not had chickenpox to develop chicken pox. The risk of developing chickenpox is very low. (Most people have already been exposed to chicken pox and acquired immunity as children.) People with shingles should be advised to avoid contact with people who have not had chickenpox, particularly pregnant women, immunocompromised people, and babies younger than a month old. Primary care staff should follow their local infection control policy and use protective equipment, disposable aprons and gloves, when there is a risk of contact with blood and body fluids.

Treating PHN

Post herpetic neuralgia (PHN) is pain that continues after the acute episode of shingles has been treated and the rash has healed. Shingles causes the nerve root to become inflamed. This inflammation can damage the nerve and this damage can cause pain signals to be sent to the brain. The pain is described as ‘shooting, stabbing or burning’ and is usually localised, on one side of the body.17 NICE guidance recommends a four step approach in primary care. This consists of self-management; assessing for depression; offering analgesia; reviewing and considering referral if necessary.16

Self-management

This consists of offering patient information leaflets,18 advising the person to wear soft loose clothing to avoid irritating skin and to consider using a film dressing as protective layer over sensitive skin. The person should be advised to use cold packs unless cold triggers pain.

Assess for depression

People who experience severe pain should be assessed for depression.19

Pain management

NICE recommends that analgesia is offered to manage pain.16 Paracetamol is the first line treatment. NICE recommends that this can be supplemented with codeine if necessary and there are no contraindications. Codeine is a mild opioid and can interact with other medicines commonly prescribed to older people such as paroxetine, sertraline and citalopram, may reduce the efficacy of codeine. The common adverse effects of codeine include nausea, vomiting, constipation, drowsiness and dizziness. Codeine use can increase the risk of falls.20 A Cochrane review examined opioid effectiveness in the treatment of neuropathic pain and concluded that there was little evidence to support their use.

Analgesic efficacy of opioids in chronic neuropathic pain is subject to considerable uncertainty.21

NICE recommends the use of drugs such as amitriptyline, duloxetine, gabapentin, or pregabalin to treat neuropathic pain.16 Standard treatment for neuropathic pain is usually a small dose of amitriptyline (10-20mg at night). This prevents the nerves conveying the pain sensation to the brain so the person no longer experiences pain, some people who have neuropathic pain do not find it effective.22

Amitriptyline, like other antidepressants can affect heart rhythm, cause drowsiness and lead to problems passing urine. As very small doses are given these seldom cause problems even in frail older people.23 Anti-epileptic drugs such as gabapentin and pregabalin are also used and act in similar ways. These can cause drowsiness, loss of balance and falls. Older people and those who are not in good health are especially at risk of side effects.17

NICE state that tramadol may be considered if acute rescue therapy is required, but should not be prescribed long-term without specialist supervision. Tramadol is a centrally acting synthetic analgesic compound . Oral tramadol 100 mg is comparable to a combination of paracetamol and codeine (1000 mg/60 mg) .It is an effective treatment for neuropathic pain however it is metabolised by the liver and excreted by the kidneys so dosage should be adjusted in older people and those with impaired renal and liver function. 24, 25 Administration of tramadol is one of the risk factors for post operative delirium in older people.26

Künig and colleagues work describes long lasting tramadol induced delirium. They comment: ‘Although tramadol may represent a well established safe therapy for chronic non-malignant pain in the elderly, these cases demonstrate that it should be applied with caution even in healthy subjects.’

Topical treatment

NICE recommends that clinicians prescribing a topical treatment such as capsacin cream or lidocaine plasters in older people or if there are concerns regarding side effects of oral medications. Topical treatments can also be used as an adjunct to oral treatment. The medication is delivered in a plaster that is applied to the skin.

Plasters containing 5 or 8% lidocaine (a commonly used local anaesthetic) are available. The 5% plaster is most effective.17 The plaster is applied to the painful area for around 12 hours and then has twelve hours without a plaster. Many people find these plasters effective but they are large. People who apply patches the limbs and trunk find them more acceptable than those who apply them to the forehead.17

Capsaicin the component of chilli peppers that causes burning is also used in patch form. A local anaesthetic is applied to the skin and then the capsaicin patch is applied for around 60 minutes by a nurse or doctor who has been trained in application. The patch is then removed but the effects of treatment – reducing pain, last for around three months Capsaicin is likely to be used when other available therapies have failed. It should not be used repeatedly without substantial documented pain relief.

Capsaicin can also be applied as a cream to intact skin. It may cause skin irritation or transient burning on application. This burning is observed more frequently when application schedules of less than 4 times daily are utilised. The burning can be enhanced if too much cream is used and if it is applied just before or after a bath or shower29

Review

NICE16 recommend follow up to check the effectiveness of treatment. The timing of follow up will be a matter of clinical judgment. Clinicians should consider referral for cognitive behavioural therapy, and/or to a neurologist or specialist pain service if pain remains uncontrolled or is interfering with daily life. Pain specialists can offer a range of highly specialised treatments including nerve blocks, transcutaneous nerve stimulators (TENS) and the newer cannaboid drugs.16

At present managing PHN is as much an art as a science as different people respond to different treatments and the evidence base is not yet established we do not yet have a lot of evidence on what treatment is most effective.

Figure five outlines NICE guidance on management of neuropathic pain.16

Preventing shingles

Vaccination reduces the risk of infection by around 72%, reduces the risk of PHN and prevents people from experiencing the debilitating effects of shingles and PHN. It is thought that the vaccination protects people for five years or more.

The vaccination programme has led to a 35% reduction of shingles and 50% reduction in PHN in individuals eligible for the vaccination. There were 17,000 fewer episodes of shingles and 3300 fewer episodes of PHN. It is important that staff working in primary care continue to encourage vaccination.

Conclusion

Shingles can cause short term discomfort and long term life changing pain. Clinicians in primary care by promoting vaccination have succeeded in reducing the incidence of shingles despite an increasing population.32 Prompt treatment with antiviral drugs is reducing the incidence of nerve pain in people who do develop shingles. These actions can make a real difference to the quality of life experienced by older people.

Linda Nazarko is a nurse consultant at West London NHS Trust

References

1. Nazarko L (2019). Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of shingles the role of the healthcare assistant. British Journal of Healthcare Assistants: 13: 1: 6-9

2. Gauthier A, Breuer J, Carrington D et al (2009). Epidemiology and cost of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in the United Kingdom. Epidemiol Infect. 137: 38-47

Oxford Vaccines Group (2019). Shingles. University of Oxford

http://vk.ovg.ox.ac.uk/shingles

3. NHS UK (2018). Shingles vaccination. NHS UK

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/shingle...

4. Green book chapter 28a. Varicella. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/governmen...

system/uploads/attachment_data/file/503773/2905109_Green_Book_Chapter_28a_v3_0W.PDF

5. Oakley A (2015). Shingles (Herpes Zoster). DermNet NZ, New Zealand

http://dermnetnz.org/viral/herpes-zoster.html

6. Pawelec G (2012). Hallmarks of human ‘immunosenescence’: adaptation or dysregulation? Immun Ageing.9:1:15.

Irwin MR, Levin MJ, Carrillo C, Olmstead R, Lucko A, Lang N, Caulfield MJ, Weinberg A, Chan IS, Clair J, Smith JG, Marchese RD, Williams HM, Beck DJ, McCook PT, Johnson G, Oxman MN (2011). Major depressive disorder and immunity to varicella-zoster virus in the elderly. Brain Behav Immun. 25:4:759-766

7. Antoniou T, Zheng H, Singh S, Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Gomes T (2014). Statins and the Risk of Herpes Zoster: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis: 58(3):350-6

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC395410...

8. Chung SD, Tsai MC, Liu SP, Lin HC, Kang JH (2014). Herpes zoster is associated with prior statin use: a population-based case-control study. PLoS One. 24;9(10):e111268.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC420884...

9. Cohen EJ (2015). Management and prevention of herpes zoster ocular disease. Cornea.;34 Suppl 10:S3-8

10 Nagel MA, Gilden D (2013). Complications of Varicella Zoster Virus Reactivation. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 15(4): 439–453.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC375270...

11. Chen N, Li Q, Yang J, Zhou M, Zhou D, He L. Antiviral treatment for preventing postherpetic neuralgia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD006866. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006866.pub3.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/1...

12. Han Y, Zhang J, Chen N, He L, Zhou M, Zhu C Corticosteroids for preventing postherpetic neuralgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Mar 28;3:CD005582. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005582.pub4.

13. NICE (2018). Shingles: Corticosteroids. CKS, London

https://cks.nice.org.uk/shingles

14. NICE (2013) Neuropathic pain - pharmacological management. The pharmacological management of neuropathic pain in adults in non-specialist settings (Full NICE guideline). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG173

NB Updated 2018

15. Nalamachu S, Morley-Forster P (2012). Diagnosing and managing postherpetic neuralgia. Drugs Aging. 29:11:863-9.

16. British Association of Dermatology (2016). Shingles (Herpes zoster infection). BAD, London

http://www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?id=128&...

17. NICE (2108). Depression. NICE, London

https://cks.nice.org.uk/depression

18. Buckeridge, D. , Huang, A. , Hanley, J. , Kelome, A. , Reidel, K. , Verma, A. , Winslade, N. and Tamblyn, R. (2010), Risk of Injury Associated with Opioid Use in Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58: 1664-1670. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03015.x

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/action/showCitForm...

19. McNicol ED, Midbari A, Eisenberg E (2013). Opioids for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Aug 29;8:CD006146

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/1...

20. Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, Cole P, Wiffen PJ. Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/1...

21. Alvarez PA, Pahissa J (2010). QT alterations in psychopharmacology: proven candidates and suspects. Curr Drug Saf. 5:1:97-104.

22. EMC (2018a). Tramadol Hydrochloride 50mg Capsules

http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/24186

23. Karen Kaye (2004) Trouble with tramadol. Editorial. Aust Prescr 2004;27:26-7

http://www.australianprescriber.com/magazine/27/2/...

24. Brouquet A, Cudennec T, Benoist S, Moulias S, Beauchet A, Penna C, Teillet L, Nordlinger B (2010). Impaired mobility, ASA status and administration of tramadol are risk factors for postoperative delirium in patients aged 75 years or more after major abdominal surgery. Ann Surg. 251:4:759-65

25. Künig G, Dätwyler S, Eschen A, Schreiter Gasser U (2006). Unrecognised long-lasting tramadol-induced delirium in two elderly patients. A case report. Pharmacopsychiatry. 39(5):194-9.

26. Derry S, Sven-Rice A, Cole P, Tan T, Moore RA. Topical capsaicin (high concentration) for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/1...

27. EMC (2014) Capsaicin

https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/888/smpc

28. Edelsberg JS, Lord C, Oster G (2011). Systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, safety, and tolerability data from randomized controlled trials of drugs used to treat postherpetic neuralgia. Ann Pharmacother. 45:12:1483-1490.

28. NHS UK (2018). Shingles vaccination. NHS UK

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/shingle...

29. Amirthalingam, Gayatri et al (2017). Evaluation of the effect of the herpes zoster vaccination programme 3 years after its introduction in England: a population-based study.The Lancet Public Health.