Shingles — also known as herpes zoster (HZ) — is a painful, blister-filled rash caused by the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV); the same virus that causes the primary infection varicella or chickenpox1. The virus affects an individual nerve and the skin surface that is served by that nerve; this is called a dermatome.1 The virus lies dormant in the dorsal root ganglia, reactivating when the immune system is weakened. This can occur at any age, but usually in older patients over 60 years, as the immune system declines in efficiency, or those who are immunocompromised, for example by chemotherapy, especially for blood cancers, solid-organ transplant, or to a lesser extent following treatment for HIV.2

In the UK, the annual incidence is estimated to be around 2 cases per 1,000 people; rising to 11 cases per 1,000 people in individuals over 80 years,3 consequently the incidence nationally is increasing due to the change in demographics; with individuals having a 20–30% risk of developing shingles during their lifetime.4 Most people only have one lifetime incidence of shingles; however, risk factors can increase this incidence. Patients presenting with shingles will almost always have had chickenpox, typically in childhood, or have been vaccinated against it1.

Women, particularly during the menopause transition, have higher rates of shingles than men, most likely due to hormonal changes to their immune system. Ethnicity plays its part, with the white population presenting more frequently, possibly due to underlying genetic factors.

It is also prevalent among people with a history of dermatological presentations, including eczema/dermatitis or trauma, and there is limited evidence that people taking statins may also have an increased risk. Psychological stress has been shown to increase the incidence, owing to stress reducing the capacity of the white cells to deal with the virus.5 However, paradoxically, smoking appears to reduce the risk by about 50%.6

The VZV is transmitted by direct skin-to-skin contact with a person who is actively shedding the virus.7 It is in this phase that shingles is contagious to unexposed individuals; once the vesicles crust over (Figure 1), the patient is no longer infectious. Although the virus can be spread, because shingles is a secondary infection, it is not possible to catch it directly from another person. However, someone who has not previously contracted, or has been vaccinated against chickenpox, can contract that disease from contact with the fluid from open vesicles (i.e., burst blisters) in active shingles.1

Symptoms typically start with a single point mild pain, which develops into tingling, prickling, burning, and itching in a localised area along one or more of the dermatomes. Other symptoms that may present, and can lead to incorrect diagnosis, include headaches, photophobia, malaise, and fever.8

Around 48 hours after onset of prodromal symptoms, an erythematous, maculopapular rash appears, with both flat, discoloured skin lesions (‘macules’) and raised bumps (‘papules’) of small fluid-filled blisters in a unilateral pattern from the body midline, correlating to the involved dermatomes. The most common areas affected are thoracic (58%), cervical (20%) and ophthalmic (10–20%) locations. The red aspect of the rash presents slightly differently on people with a darker pigmentation, decreasing the prominence of the red/pink background upon which the vesicles protrude. The vesicles are initially clear, but eventually cloud, rupture, crust and involute. In immunocompetent patients, the crusting occurs around day 7–10, with full resolution in 2–4 weeks.

In patients who are immunocompromised, this can take longer and be more widespread, owing to the immune system’s reduced capacity to deal with the virus.9 Scarring and pigmentation can persist if deeper epidermal and dermal layers have been compromised by excoriation (skin-picking), secondary infection, or other complications.10

Complications can occur in all patients, but the prevalence and severity are higher in those patients who are immunocompromised. Some patients experience a persistent or recurrent pain in the involved distribution, known as post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN).

Post-herpetic neuralgia

Post-herpetic neuralgia is the most common complication of shingles and defined as pain persisting for more than 90 days after onset of the rash, owing to nerve damage.11 It occurs in 10–13% of patients aged 60 years and over, and it is estimated that 27% of patients experienced PHN at 3 months.12

PHN pain varies in severity and can be constant, intermittent, burning, stabbing, or sharp shooting pain with hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to feeling pain) or allodynia (extreme sensitivity to touch), persisting beyond the healing of herpetic skin lesions.13 Anecdotally described as ‘like a knife being thrust into the skin and I cry out in pain’, with the allodynia arising from ‘a brush of a towel or a blow of air on naked skin’.

PHN risk and severity is linked with older age, rash severity, immunity status, and the extent of trigeminal or ophthalmic rash, with PHN lasting for around 3–6 months, with typically the severity declining with time to a sharp ache, on some occasions this can last for years.14

Treatment

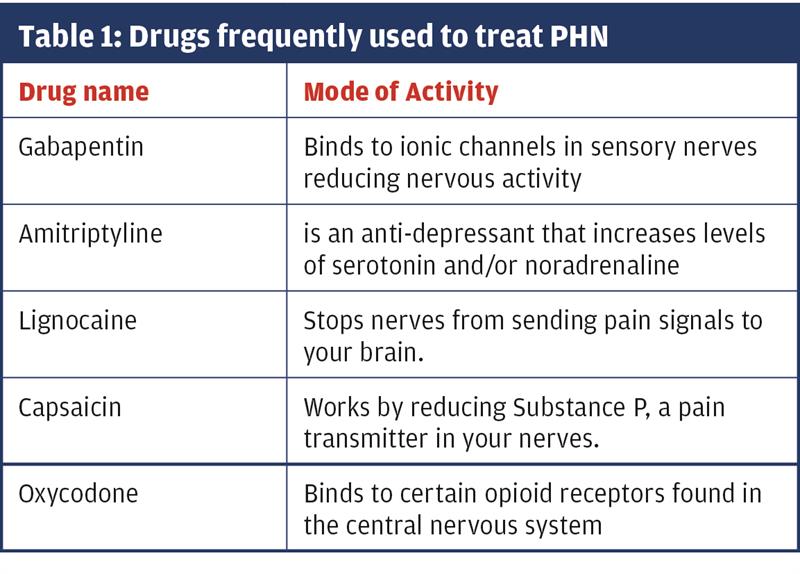

The VZV can be weakened by high doses of antivirals, for example acyclovir, while management of the pain usually involves antiepileptic drugs (like gabapentin); tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline); and/or opioid analgesics (oxycodone). Local application of lignocaine 5%, and 8% capsaicin patches can also help (Table 1). As these drugs work in different ways, they may complement each other and have an additive effect on easing pain better than alone.15

Because of their nature, many of these drugs take weeks to have an effect. The best approach is to start with the swiftest action (e.g. gabapentin or oxycodone), then reduce the dose and add slower acting drugs, like amitriptyline for longer-term use. But great care must be taken with these medications because of their addictive nature, and detailed advice should be given to the patient about possible side-effects.15

Because the damaged peripheral nerves are hypersensitive, ‘as if the top layer of skin has been removed’, adding a physical barrier over the affected area can prove useful. Two or more layers of domestic cling film reduces the pain and lessens, to a certain degree, the reliance on painkillers. This can be worn for 24 hours a day, and with time reduced as the pain subsides. It is thought that this allows clothes to slide over the skin without irritating. Loose-fitting cotton clothes are best to reduce irritation and pain, while relief can be achieved by cooling the affected area with ice cubes (wrapped in a plastic bag), or by having a cool bath.16

PHN and the immunocompromised

While age is a progressive risk factor, immunosuppression significantly increases the incidence of HZ complications and disease severity2. A nation-wide retrospective study found the risk of immunocompromised patients (>18yrs) were almost twice as high compared to immunocompetent subjects, and the risk increased with the degree of immunodeficiency.17

Preventative vaccination

The UK was the first European country to introduce a national immunisation programme for shingles for 70-year-olds, with a catch-up programme for 71–79 year-olds. GPs were encouraged to deliver the programme alongside seasonal influenza vaccination, and in that year, coverage ranged from 50 to 64% across the UK, but uptake has declined ever since18. The programme has been shown to have a significant impact in reducing the incidence of HZ, showing a 34% reduction in the population studied, and a near 50% reduction in PHN. However, the uptake of the vaccination was more likely if proactively offered in primary care.18

Zostavax (MSD) is a live vaccine given as 1 dose and this has been shown to reduce the incidence of shingles by 38%. If shingles does develop, the symptom severity is greatly reduced, and the incidence of PHN drops by 67%. In the 5 years after the vaccine programme was introduced into the UK, there was an estimated 40,500 fewer zoster consultations and 1840 fewer zoster hospitalisations.18

Shingrix (GSK) is a non-live vaccine given as 2 doses, 2 months apart. Since September 2021, it has been available as an alternative shingles vaccine for use in patients where Zostavax is clinically contraindicated. Shingrix may be used in immunocompromised individuals and may confer greater protection against HZ and PHN than the original live-attenuated virus in all patient populations. Preventative vaccination of at-risk populations may ultimately prove to be the safest way to lessen the significant morbidity associated with PHN.19

Given the demonstrated impact of the vaccination programme, the benefits need to be effectively communicated to health professionals, and to the general public, especially those about to undergo chemotherapy to maximise protection from this potentially debilitating condition in those most at risk.20

The NHS has developed a shingles vaccination toolkit for improved uptake and lays out clearly information about the vaccine and the benefits it can bring.21 More details of the vaccination programme for healthcare professionals can be found at the UK Health Security Agency website.22

Specialist nurse perspective

Prevention is undoubtedly the best approach to dealing with shingles. Working as a specialist haematology cancer nurse, with a severely immunocompromised patients, I have seen first-hand the unpleasantness of a shingles infection, and the debilitating pain that PHN can bring. Up until recently only Zostavax was available, which was unsuitable for this group of patients, as it could potentially triggered a full shingles infection.

However, Shingrex is now available, but still only for the 70-80-year-old age group. Consequently, there remains a large group of vulnerable people missing out on this protection, those with chronic cancers and those on chemotherapy treatment or post-transplant. Hopefully, access to the non-live vaccinations will become more accessible, as awareness of the consequences of shingles on this vulnerable population becomes better known.

Dr Graham F. Cope, Freelance Medical Writer

Charlotte Bloodworth, Advanced Nurse Practitioner in Haematology, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff

References

1. CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2019. Shingles (herpes zoster). transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/about/transmission.ht... (accessed 26 April 2022).

2. McKay SL, Guo A, Pergam SA, Dooling K. Herpes Zoster risk in immunocompromised adults in the United States: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis; 2020 71(7): e125–e134, doi: org/10.1093/cid/ciz1090.

3. Le P, Rothberg M. Herpes zoster infection. BMJ; 2019 k5095. doi:10.1136/bmj.k5095.

4. Zorzoli E, Pica F, Masetti G, et al. Herpes zoster in frail elderly patients: prevalence, impact, management, and preventive strategies. Aging Clin Exp Res 2018; 30: 693–702. doi:10.1007/s40520-018-0956-3.

5. Bond G, Panesar P. (2021) Case-based learning: shingles. Pharmaceutical J 306; No 945: 306 (7945): doi:10.1211/PJ.2021.20208674

6. Ban J, Takao Y, Okuno Y, et al. Association of cigarette smoking with a past history and incidence of herpes zoster in the general Japanese population: the SHEZ Study. Epidemiol Infect; 2017 145(6):1270-1275. doi:10.1017/S0950268816003174

7. Kaye K. Herpes zoster. MSD Manual professional version. 2019. https://www.msdmanuals.com/en-gb/professional/infe... (accessed 29 April 2022).

8. Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. Recommendations for the management of Herpes Zoster. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44 Suppl 1: S1–26. doi:10.1086/510206

9. Ahmed A, Brantley J, Madkan V, et al. Managing Herpes Zoster in immunocompromised patients. Herpes; 2007. 14: 32–6.

10. Cukic V. The uncommon localization of Herpes Zoster. Med Arch 2016; 70: 72–5. doi:10.5455/medarh.2016.70.72-75

11. Sampathkumar P, Drage L, Martin D. Herpes Zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clin Proc 2009; 84: 274–80. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61146-4

12. Passmore P, Kerr E. Shingles and postherpetic neuralgia. Geriatric Med 2007; https://www.gmjournal.co.uk/shingles-and-postherpe... (accessed 29 April 2022).

13. Aggarwal A, Varun Suresh V, Gupta B, et al. 2020. Post-herpetic neuralgia: A systematic review of current interventional pain management strategies. J Cutan Aesthet Surg; 13(4): 265–274. doi: 10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_45_20.

14. Jung BF, Johnson RW, Griffin DRJ, et al. Risk factors for postherpetic neuralgia in patients with Herpes Zoster. Neurology; 2004 11, 62(9): 1545–51. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000123261.00004.29

15. Johnson RW, Alvarez-Pasquin MJ, Bijl et al. 2015. Herpes Zoster epidemiology, management, and disease and economic burden in Europe: a multidisciplinary perspective. Ther Adv Vaccines; 3:109-20.

16. Tidy C. 2020. Postherpetic Neuralgia. https://patient.info/skin-conditions/shingles-herp... (accessed 02 May 2022).

17. Schröder C, Enders D , Schink T , Riedel O. 2017. Incidence of Herpes Zoster amongst adults varies by severity of immunosuppression. J Infect; 75(3): 207-215. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.06.010.

18. Bricout H, Torcel-Pagnon L, Lecomte C, Almas MF, Matthews I, Lu X, et al. 2019. Determinants of shingles vaccine acceptance in the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE; 14(8): e0220230. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.022023

19. Gruver C, Guthmiller KB. 2021. Postherpetic Neuralgia. National Library of Medicine. StatPearls Pub. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493198/ (accessed 29 April 2022).

•20. Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, Keel P, et al. 2018. Evaluation of the effect of the herpes zoster vaccination programme 3 years after its introduction in England: a population-based study. Lancet Pub Health; 3: e82–90. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30234-7. (accessed 26 April 2022).

21. NHS. Shingles vaccination programme toolkit for improving uptake https://www.england.nhs.uk/london/our-work/immunis... London Region Immunisations Team. https://www.england.nhs.uk/london/wp-content/uploa... (accessed 29 April 2022).

22. UK Health Security Agency. 2022. Vaccination against shingles Information for healthcare practitioners. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/shingles-vaccination-guidance-for-healthcare-professionals. (accessed 29 April 2022).