If a nurse is presented with a patient who smokes, they can advise them to stop smoking. If a patient is overweight, nurses can support them to slim down. But if the cause of a patient’s illness isn’t just a lifestyle choice, but the roof over their head, the solution to the problem is out of their hands, and proof that the cost of Britain’s housing crisis isn’t purely financial.

The link between living conditions and health was recognised long before the foundation of the NHS, with Aneurin Bevan, the architect of the health service, using the title of Minister for housing and health. Recent parliamentary activity could bring this question to the fore for nurses and other healthcare professionals.

The Conservatives’ Housing Bill, set to go through its final stages in early March, contains a provision nicknamed ‘pay to stay’. This means families in social housing with a combined income of over £30,000, or £40,000 in London, will be required to pay close to market rates on social housing. In 2014/15, the average (mean) rent (excluding services but including Housing Benefit) for households in the social sector was £99 compared with £179 per week in the private rented sector.

This has sparked concerns that many people previously living in well-maintained social housing may be forced into low quality, cheap private sector properties, which could damage their health. ‘More people will end up in cold homes,’ said Merron Simpson, CEO of the NHS Alliance and former head of policy at the Chartered Institute of Housing. ‘Not only that but they will end up being more isolated, so there will not be the support services available for those that are more vulnerable. There will be a number of health factors, not just cold homes. There is a real danger those people will have to find whatever is available.’

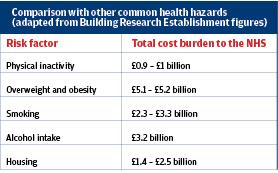

In 2014/15, 61% of people in the private rented sector said they experienced an issue such as damp, mould, leaking roofs or windows, electrical hazards, animal infestations and gas leaks, and more than a tenth said their health had been affected by this.1 This means poor quality housing is up there with smoking, alcohol, and obesity in terms of its cost to the NHS. ‘Private rental properties come in a variety of different states,’ says Ms Simpson, ‘but by far the worst conditions come in the private rented sector.’

Cold housing

The difference between legal requirements and standards between the private and social rented housing sectors can lead to tenants of privately rented properties losing out when it comes to quality housing.

‘There is no legal requirement for a landlord to insulate their property, and there is no legal requirement for a landlord to install a fuel efficient central heating system,’ says Dan Hopewell, director of knowledge at the Bromley-By-Bow community centre, an organisation in East London famed for its use of social prescribing. ‘The problem is, in the private sector, there is not a lot of incentive to spend money on insulation and central heating, as they are not the one paying the bills. So there is a big problem with this in the private rental sector. Luckily in the social rented sector, there is a much stronger emphasis on values, and there is a much stronger push in bringing properties up to what is called “decent home status”.’

Living in a cold home can have a severe impact on respiratory health. One study cited by the Marmot Review Team’s report into the health impacts of housing found that found that consultations in general practice for respiratory tract infections can increase by up to 19% for every one degree drop in the winter months.2 Worryingly, a cold home can prove fatal as the days grow shorter. Evidence suggests that more than one in five excess winter deaths in England and Wales are attributable to cold housing.

‘The impact of cold housing on health and the stresses brought on by living in fuel poverty have been recognised for decades by researchers, medical professionals and policy makers alike,’ says the review’s lead author, Professor Michael Marmot of the department of epidemiology and public health at University College London. ‘At the same time, it is an issue that often gets dismissed as the “tough nature of things” because our housing stock is old and cold housing is so widespread that many have come to regard it as a normal state of affairs.’

‘Every day, we hear from parents up and down the country living in fear that damp, gas or electrical hazards are putting their children in danger, but feeling powerless to do anything about it. This has to stop,’ says Campbell Robb, chief executive of housing charity Shelter.

Mental health

Living in low quality housing is a known factor in the development of mental health issues. Research from Shelter3 found that almost one in three adults, equivalent to roughly 15 million people, said that housing costs had caused stress and depression in their family. The charity also stated that the stress of living in cold, damp conditions can also impact on mental health as families.

According to the Marmot report,2 one in four adolescents living in cold housing are at risk of multiple mental health problems, compared to one in 20 adolescents who have always lived in warm housing. It also showed that residents with bedroom temperatures at 21°C are 50% less likely to suffer depression and anxiety than those with temperatures of 15°C.

‘The impact this stress could have on family members as well as people’s long term health is a real concern, especially if this leads to a generation of people reliant on prescription drugs,’ adds Mr Robb. ‘As more and more people succumb to the pressures of keeping up with basic housing costs, they too could find their health suffering, putting even more pressure on an already overstretched health service.’

Occupancy

Resident numbers in each property need to be just right to ensure the healthiest living conditions. Very much a ‘Goldilocks’ issue, both under and over occupation of a property can cause health problems for tenants.

Living in cramped conditions can place strains upon a person’s mental health, as well as increase the risk of the spread of infectious disease. According to Mr Hopewell, this is a particularly common problem in London, where space is at a premium, encouraging landlords and tenants to maximise the use of property. He said that there was anecdotal evidence of one terraced home in his area that had as many as 55 people living in it.

On the other hand, under occupation is a leading cause of fuel poverty, says Mr Hopewell. The patient may live in a three-bedroom house alone, and cannot afford to keep the large property adequately heated, leaving them vulnerable to the detrimental effects of living in a cold house. This is often caused by people wishing to hold onto their property due to financial incentive, or a lack of alternative housing in the local area, despite the home not being as suitable to the occupants needs as it once was.

According to the English Housing survey,4 the overall rate of overcrowding in England in 2014-15 was 3%, unchanged from 2013-14, with 675,000 households living in overcrowded conditions. In comparison, 36%, unchanged from 2013/14, with around 8.2 million households living in under occupied homes.

What can nurses do

The first thing to bear in mind, says Mr Hopewell, is that nurses and healthcare professionals are not a substitute for housing workers. Rather, it is important that healthcare professionals who recognise symptoms and conditions arising from poor quality housing and understand where they can direct patients to.

Ms Simpson says ‘A solution could be the establishment of a single referral pathway into a local system for improving homes,’ says Ms Simpson. ‘There is also potential for home improvements such as boilers to be prescribed by healthcare professionals.

‘That doesn’t mean the NHS has to pay for it, but money could come from a number of different places. District nurses in particular, because they do home visits, can relay information about the home environment to the surgery.

In some areas there are more advanced information systems that allow general practices to hold data on the living conditions of patients.’

Mr Hopewell also highlight the valuable role that integrated services can play in tackling the problem. He states that Bromley-by-Bow uses opportunities such as jabs and appointments to have workers from other sectors come and talk to patients. Many who take up the flu vaccine, such as those with special needs and the elderly, will also be vulnerable to the worst effects of poor housing.

According to NICE guidance,5 healthcare professionals should be aware that the link between some minority ethnic groups and deprivation may mean that some of these groups are more likely to live in cold homes. Other groups, including recent immigrants from warmer climates, could also be particularly vulnerable during their first few years in the UK. For example, they may be more likely to live in poor quality housing and they have to negotiate an unusually complex energy market to heat their homes.

It is still too early to tell if legislation will result in a large shift of vulnerable people into poor quality housing. However, the problem of people forced by circumstance to live in unsafe, cold, and damp properties is undeniably a problem for both the NHS and our wider society. Maybe this is the signal to knock down the wall between social problems and health ones, and work towards a more open plan service.

| The Housing and Planning Bill |

|

References

1. People living in bad housing – numbers and health impacts. NatCen Social research

2. Marmot Review. The health impacts of cold homes and fuel poverhttp://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/projects/th...

3. Shelter. Housing costs cause depression.http://england.shelter.org.uk/news/previous_years/...

4. Department of Housing. English Housing Survey 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/english-...

5. NICE. NG6: Excess winter deaths and illness and the health risks associated with cold homes

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng6