The COVID-19 pandemic continues and as the Government seeks to avoid a second wave of infections people working in or entering hospitals are required to wear surgical masks. Masks or face covering are required when shopping or using public transport. The BBC reports that factories in south Wales and Lancashire have started making ‘high quality’ face coverings as part of a push to produce a million a week.1 The French government has ordered 2 billion disposable face masks from China.2

What happens to a mask when it is discarded?

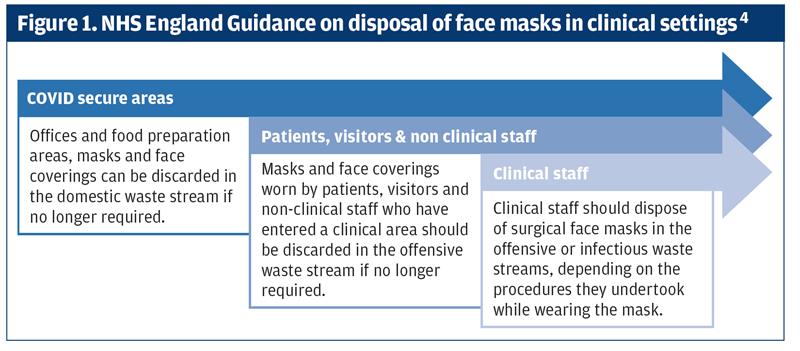

In domestic settings disposable face masks should be put in domestic waste.3 Figure 1 outlines the disposal of masks in clinical settings including nursing homes. It is estimated that the NHS will use 15 million orange bags a month during the COVID-19 response.4

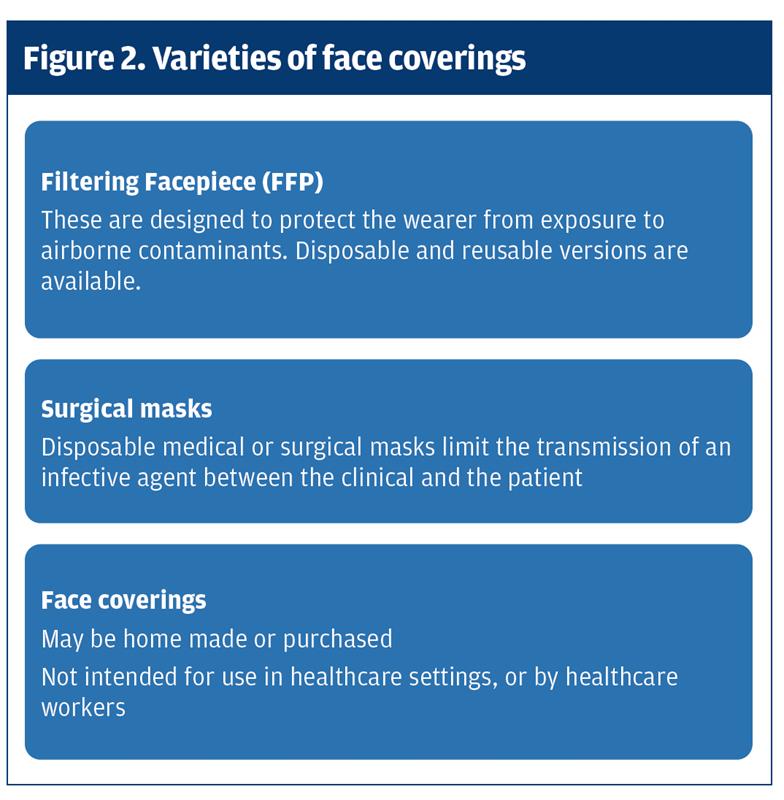

These disposable masks will eventually end up in landfill and will take an estimated 450 years to break down. Eric Pauget a French politician wrote to the French President Emmanuel Macron about this recently, describing the use of disposable PPE as ‘an ecological time bomb’.5 Not all disposable masks end up in landfill and significant numbers are polluting the world’s oceans. Oceans Asia recommends that whenever possible people wear reusable face coverings to reduce the environmental damage of PPE.6In clinical settings medical face masks offering differing levels of protection dependent on the level of potential exposure are required. In January the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that approximately 89 million medical masks were required each month to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic.7 Figure 2 provides details of face masks.

How effective are masks and face coverings?

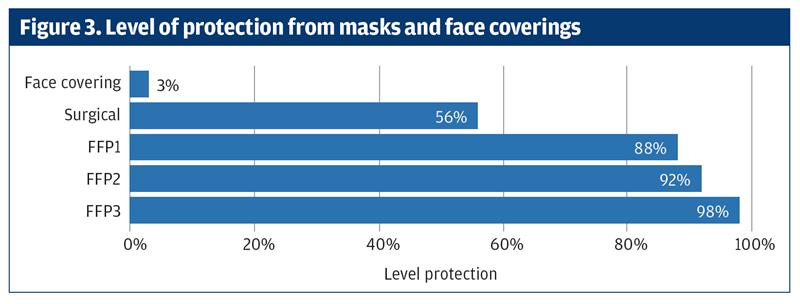

FFP masks must meet European EN149 standards. There are three levels of protection, FFP1, FFP2, FFP3 and these levels are determined by measuring the leakage of all particles into the interior of the mask. These are, 22% for FFP1. 8% for FFP2, 2% for FFP3.8

In 2015 MacIntyre and colleagues carried out a study to compare the effectiveness of cloth masks versus surgical masks in a hospital. The study involved 1607 healthcare workers. The healthcare workers wore the masks for four weeks whilst performing aerosol generating procedures such as obtaining sputum, airway suctioning, intubation and bronchoscopy. They found that particles penetrated 44% of surgical mask and almost 97% of cloth masks.9 Figure 3 illustrates the efficacy of different types of masks and face coverings.

Its vitally important that staff providing healthcare receive equipment to protect them when they are caring for people with infections such as COVID-19 but how do we protect staff without creating an environmental catastrophe?

Reduce, re-use, recycle

The principles of reducing the environmental impact of waste are to reduce, reuse and recycle. In the midst of a pandemic reducing the use of face masks in healthcare settings is not an option but can they be re-used?

When the COVID-19 pandemic first emerged there was a global shortage of facemasks and other PPE, this led to researchers exploring the possibility of re-using facemasks.10 Facemasks must be decontaminated to enable them to be re-used. Research has been carried out on FFP2 masks also known as N95 masks. Although manufacturers recommend their disposal after close contact with a patient with an infectious disease, after use during an aerosol-generating procedure or on contamination with bodily fluids, they maintain function for 8 hours of continuous or intermittent use and extended use in combination with appropriate hand hygiene and contamination-limiting practice is considered minimal risk.11,12

Decontamination procedures must maintain the effectiveness of the mask, provide effective disinfection and cause no harm to the user.13 Trials indicate that microwave irradiation, microwave-generated steam and moist heat incubation can compromise the physical integrity of respirator components. Treatment with bleach-exposed users to odour and release of chlorine gas on exposure to moisture. Treatment with hydrogen peroxide gas plasma, autoclave, 160°C dry heat, 70% isopropyl alcohol and soaking in soap and water may affect the efficiency of the mask. Using, ethylene oxide, dry oven heating and hydrogen peroxide vapour may preserve of function and integrity of the mask.10

Recycling face masks in the UK is problematic, as they are not recyclable through conventional recycling facilities.14 It is possible to pay specialist recyclers to recycle face masks that have not been used in clinical settings.15 In the Netherlands, microbiologists are working with recyclers to sterilise masks so that they can be reused. Clinicians place used masks in recycling bins and these are collected. The masks are sterilised at 121 C to kill the coronavirus microorganisms. The masks remain usable after this process and they are packed in boxes and returned to the hospitals within 24-48 hours. The sterilisation method has been approved by the Dutch health authority RIVM.16

Why worry about the environment in the midst of a pandemic?

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to unprecedented use of personal protective equipment (PPE) globally. In the UK we are using many millions of facemasks and those facemasks may end up in landfill where, as mentioned previously, they can take almost 500 years to degrade. Some are ending up in the oceans and degrading the marine environment.

Environmental pollution has detrimental effects on human health. Globally 23% of deaths and 22% of disability is related to pollution. Pollution increases the risk of cancer, cardiovascular and respiratory disease, it affects mental health and the health of those who are yet to be born.17

Those who are most at risk from COVID-19 are people who have long term conditions18 and in seeking to protect ourselves and our patients we may well be increasing the risks of death and disability in the longer term.

How to minimise environmental damage during the pandemic

The Government has much to do to prevent a second wave of COVID-19, and the use of PPE is an important part of that strategy. However we cannot continue to dump masks and other PPE and degrade our environment further. Government must lead the way in determining how to decontaminate and recycle the PPE that we are using. We cannot leave this for future generations to clean up.

Linda Nazarko, Consultant Nurse, West London NHS Trust

References

1. BBC. 2020. Coronavirus: £14m for firms to make ‘million face masks’ a week. BBC News.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-53474998

2. France 24. La France a commandé près de 2 milliards de masques en Chine.

https://www.france24.com/fr/20200404-la-france-a-c...

3. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 2020a. Guidance: Coronavirus (COVID-19): disposing of waste.

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/coronavirus-covid-19-d...

4. NHS England. 2020. COVID-19 waste management standard operating procedure 29 June 2020, Version 2. NHS England, London.

https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/...

5. Pauget E. 2020. Letter to Emmanuel Macron.

https://ericpauget.fr/lettre-a-emmanuel-macron/

6. Oceans Asia. 2020. PPE and the negative effects on the environment. Ocean’s Asia.

http://oceansasia.org/reusable-masks/

7. WHO. 2020a. Advice on the use of masks in the community, during home care and in health care settings in the context of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. World Health Organization. Interim guidance 29 January 2020.

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/330987/WHO-nCov-IPC_Masks-2020.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

8. 3M. 2020. Legislation and Standards

https://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/433598O/europe...

9. MacIntyre CR, Seale H, Dung TC, Hien NT, Nga PT, Chughtai AA. A cluster randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4)

doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006577.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC44209...

10. Garcia Godoy LR, Jones AE, Anderson TN, et al. Facial protection for healthcare workers during pandemics: a scoping review. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(5):e002553.

doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002553

https://gh.bmj.com/content/5/5/e002553

11. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. CDC - Recommended Guidance for Extended Use and Limited Reuse of N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirators in Healthcare Settings - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic [Internet]. Pandemic Planning. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hcwcontrols/recom...

12. Fisher EM , Shaffer RE . Considerations for recommending extended use and limited reuse of filtering facepiece respirators in health care settings. J Occup Environ Hyg 2014;11:D115–28.doi:10.1080/15459624.2014.902954

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24628658

13. Institute of Medicine. Reusability of Facemasks During an Influenza Pandemic: Facing the Flu [Internet], 2006. Available: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/11637/reusability-of-f...

14. Murray JS. Recyclers urge public not to recycle face masks and other PPE

https://www.businessgreen.com/news/4014663/recycle...

15. Zero Waste. https://zerowasteboxes.terracycle.co.uk/products/d...

16. Reintjes Martijn 2020. Second life for 48 000 mouth masks each day. Recycling International.

https://recyclinginternational.com/corona-virus/se...

17. Vineis P, Fecht D. Environment, cancer and inequalities—The urgent need for prevention’: European Journal of Cancer

Volume 103. November 2018. Pages 317-326

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/...

18. NHS UK. People at higher risk from coronavirus.