A new review by Public Health England has revealed that hundreds of thousands of people might be hooked on prescription drugs. The findings included the fact that 1.2 million people had been taking opioid-based painkillers for at least a year, with half of these having been taking them for three years.

Given that the drugs are only supposed to be used for short periods of time, it is easy to say why health chiefs are alarmed by the findings. Health Secretary Matt Hancock, mindful of the US opioid crisis, described it as a wake-up call’. But according to the latest figures from the ONS, we could be on our way, as‘accidental poisoning’ has replaced suicide as the biggest killer of middle-aged men.

Suicides in the UK

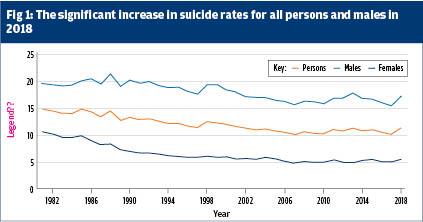

There were 6,507 suicides registered in the UK in 2018, an age-standardised rate of 11.2 deaths per 100,000 people. The latest rate is significantly higher than that in 2017 and it represents the first increase since 2013. 4,903 of registered deaths, three-quarters in 2018 were among men, a statistic that has remained the same since the mid-1990s. The UK male suicide rate of 17.2 deaths per 100,000 denotes a significant increase from the rate in 2017; in the UK, for females, the rate was 5.4 deaths per 100,000, a constant over the past 10 years.

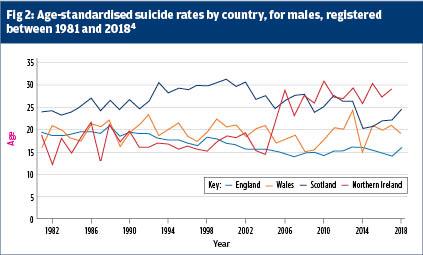

Scotland had the highest suicide rate with 16.1 deaths per 100,000 persons (784 deaths). This is followed by Wales with a rate of 12.8 per 100,000 (349 deaths), England has the lowest rate with 10.3 deaths per 100,000 (5,021 deaths); data for Northern Ireland is yet to be published.

Men aged 45 to 49 years had the highest age-specific suicide rate (27.1 deaths per 100,000 males); compared to their female counterpart, the age group with the highest rate was also 45 to 49 years, at 9.2 deaths per 100,000. Despite having a low number of deaths overall, the rates among the under 25s have generally increased in recent years, particularly in the 10 to 24-year-old female age group where the rate has increased significantly since 2012 reaching its highest level with 3.3 deaths per 100,000 females in 2018.

The most common method of suicide in the UK was hanging (and this has been the case for previous years). Hanging accounts for 59.4% of all suicides among males and for female suicide this is 45.0%. Figure 1 details the significant increase in suicide rates for all persons and males in 2018.

In figure 2 the suicide rate for males in England is provided. This shows how in 2018 this had significantly increased.

Drug poisoning

From a toxicological perspective the World Health Organisation1 defines poisoning as ‘the state resulting from the administration of excessive amounts of any pharmaceutical agent’. Vale and Bradberry2 suggest that drug poisoning denotes exposure to a substance which is a danger to health or life.

Drug poisoning deaths can involve a broad range of substances, these can include controlled and non-controlled drugs, prescription medicines (either prescribed to the individual or acquired by other means) and over-the-counter medications. As well as

deaths from drug abuse and dependence, the data associated with drug poisoning include accidents and suicides that involve drug poisonings along with complications of drug abuse including deep vein thrombosis or septicaemia as a result of intravenous drug use. The data does not include other adverse effects of drugs, such as, anaphylactic shock or accidents that are caused by a person being under the influence of drugs. Over 50% of all drug poisoning deaths involve more than one drug and occasionally this also includes alcohol, often it may not be possible to determine which substance was primarily responsible for the death.

Male deaths and drug poisoning

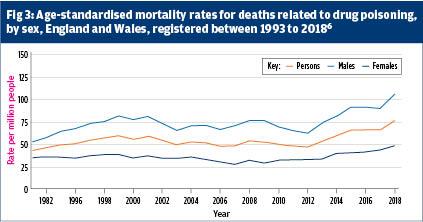

The rates of male deaths related to drug poisoning have doubled since 1993. Male deaths linked to drug poisoning have now become the biggest killer of men aged 35 to 40 years in the UK. Suicide, once the leading cause of death in middle-aged men, has been eclipsed by drug overdose. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has revealed that men in this age group are now more likely to be killed by drug overdoses or accidental poisonings.

The number of deaths registered from drug use in 2018 was the highest since records kept by ONS began in 1993. The data demonstrated the biggest year-on-year percentage increase. Drug poisoning deaths had been previously related to opiates such as heroin and morphine however, recently there were also increases in deaths across a wider variety of substances including cocaine and new psychoactive drugs (known also as ‘legal highs’).

In England and Wales since 1993 the rates of male deaths linked to drug poisoning have doubled (see figure 3). In 2018 in England and Wales, there were 4,359 deaths relating to drug poisoning. This was 603 more than in 2017 when there were 3,756 (a 16% increase). These data reveal a statistically significant increase in the drug poisoning rate, with 76.3 deaths per million people in 2018, compared with 66.1 deaths per million in 2017.

Rates of drug-related poisoning have generally been on an upward trend in England and Wales since 2012, something previously attributed to an increased rise in heroin deaths. Across Northern Europe (including Scotland and Northern Ireland) higher than average drug-related mortality rates have also been reported over the last several years.3,4

In 2018 men accounted for more than two-thirds of drug poisonings, with 2,984 male deaths compared to 1,375 female deaths. In 2018 there was a significant increase in male deaths from 89.6 per million males in 2017 to 105.4 in 2018. The female age-standardised rate increased for the ninth consecutive year to 47.5 deaths per million females in 2018, this was up from 42.9 deaths in 2017. The recent increase in the female rate was not statistically significant when compared to the previous year.

Most drug poisoning deaths in 2018 were reported to have an underlying cause of accidental poisoning (80% of male deaths and 67% of female deaths); followed by intentional self-poisoning (16% of male deaths and 30% of female deaths). The remaining deaths were caused by mental and behavioural disorders as a result of drug use (3% for males and females) or assault involving drugs (less than 1% for males and females).

Drug poisoning deaths as a result of drug misuse have accounted for two-thirds of deaths in the last ten years. A drug misuse death is one where either the underlying cause is drug abuse or drug dependence, or the underlying cause is drug poisoning and any of the substances controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 are involved. In 2018 there were 2,917 deaths relating to drug misuse out of a total of 4,359 drug poisoning deaths.4 The rate of death relating to drug misuse in 2018 demonstrates a statistically significant increase when compared to 2017.

Trends associated with deaths from selected drugs

Since 2006 over half of all drug poisonings have involved the use of an opiate. A total of 2,208 drug poisoning deaths in 2018 mentioned on the death certificate (51% of all drug poisoning deaths) the use of an opiate, equating to a rate of 38.7 deaths per million people. This has significantly increased when compared to 2017 with a rate of 34.9 deaths per million.

The most frequent opiates mentioned in 2018 were heroin and morphine with 1,336 drug poisoning deaths mentioning either one of these substances. This equated to a rate of 23.4 deaths per million people, demonstrating a statistically significant increase when compared to the rate in 2017 (20.5 deaths per million).

Deaths associated with the use of cocaine have risen for the seventh consecutive year reaching their highest level. 637 deaths were related to cocaine in 2018, this is nearly double the number of deaths registered a few years earlier in 2015, with 320 deaths. Deaths that mention cocaine show a rising trend since 2011, in which they have increased from 1.9 deaths per million.

There were 125 deaths in 2018 involving new psychoactive substances, which equates to a rate of 2.2 deaths per million people. This is a statistically significant increase from the 61 deaths recorded in 2017 (1.0 per million) and a return to the level seen in 2016 when there were 123 deaths (2.1 per million). The Psychoactive Substances Act 2016 established a blanket ban on the importation, production or supply of most psychoactive substances.

Reducing deaths

The data produced by the ONS can help decision makers who are working towards protecting those people who are at risk of dying from drug poisoning the data is a prompt signalling of a need to provide strategy and direction. Deaths from drug misuse among men aged between 40 and 49 are significant. An awareness of the incidence of deaths associated with drug poisoning. By raising awareness nurses can help commissioners of services to focus efforts and support those who are at risk, as well as targeting areas such as the North East of England where risk and incidence is highest.4

It is clear that middle aged men are at high risk of death by drug poisoning and this appears to have gone unnoticed and does not seem to have been discussed by health and social care practitioners, meaning that many health and social care practitioners are oblivious to the issue. There are concerns of a looming opiate crisis. Investing in evidence-based measures, in treatment programmes to reduce deaths and understanding why drug poisoning has become the biggest killer in middle aged men is an urgent unmet public health need.

In order to seriously address overall harm, The Transform Drug Policy Foundation5 suggest that drug policy should be assessed using a wider range of metrics such as the impacts on crime, health, international development, security, human rights, the environment and the economy should all be front and centre when investigating new approaches and evaluating current ones. A more holistic strategy, a public health strategy combined with a shift away from criminal justice responses, is the way to ensure the drug control system accomplishes its original aim of protecting the health and welfare of societies.

Nationally, there are shortages in skilled professional staff and this, alongside the disconnection between health and addiction services, means that those men who are living with multiple health needs cannot be heard and properly treated. Separating NHS mental health services from addiction services and moving the emphasis away from harm reduction to abstinence-based recovery is devastating lives and promoting the increase in drug-related deaths. A more compassionate, harm-reduction approach has been advocated for many years but still the government promotes a tough position around law enforcement, as it simultaneously reduces and sustains cuts to the budgets of local authorities.

Conclusion

Whilst the bulk of this article provides a plethora of data demonstrating a rise in the number of deaths in men related to drug poisoning are clearly shocking, it must be remembered that behind these deeply troubling figures there are men, families and communities. The impact a death related to drug poisoning has on these families and communities is unmeasurable.

There must be an acknowledgment of the up-to-date data produced by the ONS who are unmistakeably indicating similar trends in avoidable deaths in men, and the key question; ‘why are more men dying from drug poisoning’ must be asked. UK health and social care policy must make a response to the needs of those men who are clearly at risk of premature death, this burning justice has to be addressed. One man dying of drug poisoning is one too many and nurses and key cross-government agencies must be committed to tackling the root causes of this abhorrent health inequality. The data provided demonstrate a public health emergency and this cannot be ignored by nurses, commissioners or the government as this is putting people’s lives at risk. Death by drug poisoning is a reality and not a faceless statistic.

Ian Peate, Professor of Nursing and Head of School of Health Studies, Gibraltar

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Mrs Frances Cohen for her help and support

References

1. World Health Organization (2014) ‘Community Management of Opioid Overdose’. World Health Organisation. Geneva

2. Vale, A. and Bradberry, S. (2016) ‘Poisoning: Introduction’. Medicine Vol 44 No 2 pp 75-75.

3. Office for National Statistics (2016) ‘Deaths Related to Drug Poisoning in England and wales: 2015 Registrations’

4. Office for National Statistics (2019a) ‘Suicides in the UK: 2018 Registrations’

5. The Transform Drug Policy Foundation (2016) ‘Will Drug use Rise? Exploring a Key Concern about Decriminalising or Regulating Drugs’

6. Office for National Statistics (2019b) ‘Deaths Related to Drug Poisoning in England and Wales: 2018 Registrations’